Opinion

Communication in Perioperative Education

|

|

In a recent meeting with the family of a critically ill patient, we deliberated about pursuing an aggressive operation to control the source of sepsis. Because the surgeon was not able to attend the meeting, a resident came in his place; at one point I asked the resident to describe the procedure in question.

To my surprise, the surgical resident described not only the technicalities of the procedure, but also outlined several additional considerations: the likely outcome, the relevant concerns, the alternative options, and how all of the above fit into the patient’s current condition. The resident spoke clearly, included relevant facts, and used language that was readily understandable to the anxious family members. Equally important, the resident’s manner was engaging and compassionate.

I later learned that this particular resident had recently participated in a communication skills training program.1 In this program, small groups used role play to practice and to generate real-time feedback. Residents assessed their own preparedness before and after the session, and they reported high satisfaction and frequent subsequent opportunities for application. In this case, I witnessed these skills used in an actual encounter, in which the resident’s communication guided decision-making and supported the family.

Communication as a Core Competency

The ACGME Milestones Project highlights aspirational goals for effective communication: to resolve concerns, to manage conflict, to help other professionals improve communication, and to demonstrate leadership in team-based care.2,3 I know very few physicians who do all of these consistently on an expert level. Yet deliberate consideration of these aspirations highlights two important questions.

First, have we constructed our educational programs with these aspirational goals in mind? An ideal program would not simply ensure competence of residents, but also distinguish between competent and expert performance and give the resident tools to push oneself further. Opportunities for practice, both in simulated and patient care environments, are necessary to hone skills. Communication skills should be practiced with the same attention that one practices technical skills. A three-step approach can be used to do this: preparing, performing the procedure, and reviewing one’s performance.4

Moreover, an effective program would offer feedback to faculty members who seek to move beyond proficiency to expert communication, so that we regularly model excellence in communication to our trainees and to the multidisciplinary healthcare team. Such a program would train faculty members to provide feedback to trainees that is specific, behavior-focused, and actionable.5

Second, do we employ communication skills as a foundational component to every other competency? In some domains, this is readily apparent: activities of Professionalism, such as mentorship, feedback, and managing ethical issues, require an exploration of behaviors, motivation, and values. And in the areas of Systems-Based Practice and Practice-Based Learning, efforts related to patient education, coordination of care, and quality improvement projects cannot be done without using language in spoken or written form. In the acute care environment, we know that leading a crisis response is rooted in leadership and facilitating teamwork, which requires effective communication.6

In performing direct patient care, potentially frustrating experiences can be managed well with a few direct words. “This airway might be difficult. Could you turn off the music and stand by in case I need a hand?” “Give me a minute before tucking the arms. For a case like this, it’s important to get better IV access.” If we think our team-members are not valuing the work we do, many times we simply need to clue them in to its importance.

We therefore consider communication to be an integral skill for the physician. In order to improve our educational programs and our own practice, two seemingly contradictory principles may guide us. These principles suggest that communication is at once something quite simple, and something profound.

Communication is Simple

Grice, in 1975, outlined the cooperative principle in conversation.7 A speaker and a listener work together to exchange information, and the speaker should do several things to be effective: provide an appropriate amount of information, say things that are known to be true, and ensure relevance to the topic at hand. Speech should be orderly and concise. These are the maxims of quantity, quality, relation, and manner.

Adherence to these mutually understood rules makes conversation easy, but a departure from the maxims shifts the burden onto the listener to make sense of what was heard. The listener must expend energy to discern useful information and interpret the meaning. Even a child can recognize statements that violate Grice’s Maxims,8, 9 but just because the maxims are intuitive does not mean that adults do them well. With intentional observation of speech in the hospital, we hear countless examples of irrelevant or poorly organized communication. We say too much, we say too little, and we say it at the wrong time.

With a moment’s pause to organize what we want to say before we say it, and with reflection about what we said, we can be our own best teacher. Our speech should be a straightforward guide to our thoughts, so that even complex ideas are easy to follow. As Mark Twain said about writing:10

“At times [a good writer] may indulge himself with a long [sentence], but he will make sure there are no folds in it, no vaguenesses, no parenthetical interruptions of its view as a whole; when he has done with it, it won't be a sea-serpent with half of its arches under the water; it will be a torch-light procession.”

It is equally important, then, to pay attention to what our listener will hear as it is to think about what we would like to say.

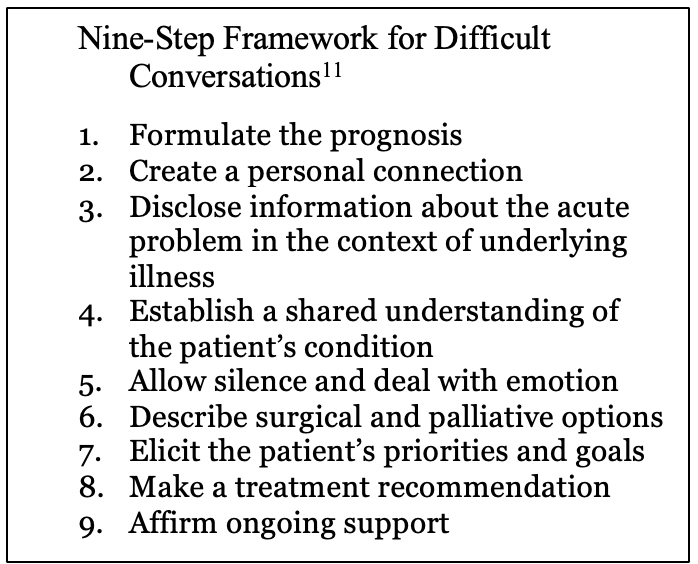

In the hospital, using a simple structure to conversations can have positive results. A nine- point framework has been recommended for surgeons who are communicating with patients about an urgent and difficult decision.11 Although following these steps may seem formulaic, the use of such guides can ground the conversation in the relevant context with due attention to the patient’s goals. Simply using a framework will get us most of the way there.

point framework has been recommended for surgeons who are communicating with patients about an urgent and difficult decision.11 Although following these steps may seem formulaic, the use of such guides can ground the conversation in the relevant context with due attention to the patient’s goals. Simply using a framework will get us most of the way there.

Communication is Profound

At the same time, our communication conveys the things most important to us: our language expresses our values and gives shape to our lives. In a preoperative patient encounter, our words describe relevant information about anesthesia care, but more importantly, they tell our patients that they are in good hands and will be taken care of.

The weight of these ideas demands that we give fastidious attention to what we say. In The Four Agreements, Don Miguel Ruiz emphasizes the importance of being impeccable with our word.12

“It is through your word that you manifest everything. Regardless of what language you speak, your intent manifests through the word… [Your word] is the power you have to express and communicate, to think, and thereby to create the events in your life.”

Language is not simply about our grammar and syntax; we must also attend to how those words are delivered. Our listener will perceive what we think about what we say by noting the pitch of our voice, the rhythm of our speech, and the energy we use. Through nonverbal communication, we convey either interest or boredom. We show our engagement in the moment. And our nonverbal communication helps patients feel valued. The physician who pulls up a chair to sit with her patient, makes eye contact, acknowledges emotions, and allows for silence will make her patient feel important.

Our words will take on gravity if we embrace them as an expression of how we regard our patients and our coworkers. When the surgeon snaps in frustration, we might respond in the voice of a team-member who understands the problem and is supportive of the shared task. When we work with headstrong trainees, we consider how we might say something to demonstrate respect and help them to be a better physician. When we encounter patients, we pause and intentionally step into the meaning of their experience.

In these seemingly contradictory ways of regarding communication as both simple and profound, we can teach ourselves to polish this critical ability and consider how to support our trainees and one another in this lifelong skill.

References

1. Nakagawa S, Fischkoff K, Berlin A, Arnell TD, Blinderman CD. Communication Skills Training for General Surgery Residents. J Surg Educ. 2019 Sep -Oct;76(5):1223-1230.

2. Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051-1056.

3. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/AnesthesiologyMilestones.pdf (accessed January 21, 2020)

4. Nakagawa S. Communication--The Most Challenging Procedure. JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Aug;175(8):1268-9.

5. Mitchell JD, Ku C, Diachun CAB, DiLorenzo A, Lee DE, Karan S, Wong V, Schell

RM, Brzezinski M, Jones SB. Enhancing Feedback on Professionalism and

Communication Skills in Anesthesia Residency Programs. Anesth Analg. 2017

Aug;125(2):620-631.

6. Howard SK, Gaba DM, Fish KJ, Yang G, Sarnquist FH. Anesthesia crisis resource management training: teaching anesthesiologists to handle critical incidents. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1992;63(9):763–70.

7. Grice, H. P. (1975). “Logic and conversation,” in Syntax and Semantics 3: Speech Acts, eds P. Cole and J. J. Morgan (New York, NY: Academic Press), 41–58.

8. Eskritt M, Whalen J, Lee K. Preschoolers can recognize violations of the Gricean maxims. Br J Dev Psychol. 2008 Sep 1;26(3):435-443.

9. Okanda M, Asada K, Moriguchi Y, Itakura S. Understanding violations of Gricean

maxims in preschoolers and adults. Front Psychol. 2015 Jul 2;6:901.

10. Doyno, Victor A. Writing "Huck Finn": Mark Twain's Creative Process. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991

11. Cooper Z, Koritsanszky LA, Cauley CE, Frydman JL, Bernacki RE, Mosenthal AC, Gawande AA, Block SD. Recommendations for Best Communication Practices to Facilitate Goal-concordant Care for Seriously Ill Older Patients With Emergency Surgical Conditions. Ann Surg. 2016 Jan;263(1):1-6.

12. Ruiz, Don Miguel. The Four Agreements: A Practical Guide to Personal Freedom, A Toltec Wisdom Book. Amber-Allen Publishing, 1997

Jonathan Hastie, MD

Jonathan Hastie, MD