Research TipsSponsored by the SEA Research Committee (Section Editor - Ted Sakai, MD, PhD, MHA, FASA) September 2023 - Invitation to the SEA Research Mentorship Program (2023-2024 Cycle)August 2023 - Invitation to the SEA Research Mentorship Program (2023-2024 Cycle)August 2022 - The Best Trainee Abstract Awards (New Program Announcement!)July 2022 - Introduction of the SEA Research Mentorship ProgramJune 2022 - Foundations and Practical AdviceMay 2022 - Foundations and Practical AdviceApril 2022 – Foundations and Practical AdviceMarch 2022 – Foundations and Practical AdviceFebruary 2022 – NoiseJanuary 2022 – Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT)November 2021 – Self Determination Theory (SDT)October 2021 – SEAd Grant ApplicationSeptember 2021 – SEA Meeting Abstract and PresentationSeptember 2023: Invitation to the SEA Research Mentorship Program (2023-2024 Cycle)The SEA Research Committee has been organizing research mentorship to the SEA members with great success! Please check out this month's tips “Research mentorship program reflection – Part 2” by Christine Vo, MD, FASA (Mentee 2022-2023 Cycle, Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center), Oluwakemi Tomobi, MD, MEHP (SEA Research Mentee: 2022-2023 Cycle, Clinical Research Scientist, West Virginia School of Medicine), Susan Martinelli, MD, FASA (Mentor 2022-2023 Cycle, Edward A Norfleet, MD '70 Distinguished Professor, University of North Carolina), Fei Chen, PhD, MEd, MStat (Mentor 2022-2023 Cycle, Assistant Professor, University of North Carolina). We are now inviting applicants to the research mentorship program in 2023-2024 cycle.

The SEA Research Mentor Program has been a phenomenal opportunity for me to explore the field of educational research with experts who’ve shown the capacity to be highly productive. A fundamental aspect of the program is the ability to review the ‘profiles’ of potential mentors to get a sense of the type of research projects they’ve been involved in and what organizations/roles they’ve served. This helped me with identifying someone I felt I could really connect with. In my role as Assistant Program Director and Medical Student Clerkship Director, I am significantly involved in overseeing the learning environment of our residents and students. After attending the SEA Workshop of Teaching, I wanted to explore the field of educational research to strengthen my competency as an educator. I had difficulty with finding a local mentor who had the capacity to provide meaningful guidance in developing and attaining my research goals while also empathizing with my busy administrative responsibilities. With Dr. ‘Susie’ Martinelli’s mentorship, I was able to implement my first educational research project and gain the confidence to initiate additional studies, with three abstracts presented at the 2023 SEA Spring Meeting. The feeling of having someone with such expertise and empathy invested in my professional and academic growth was revitalizing and gave me the confidence to push myself beyond what I could only imagine. If there is any inkling of interest in educational research, I highly recommend enrolling in the SEA Research Mentor Program. The mentors are thoughtfully selected to provide the highest quality professional relationship with meaningful feedback, productive discussions, and access to opportunities that may not be readily available at your home institution. The only regret I have is that I didn’t apply for this program sooner!

“Mentoring is a brain to pick, an ear to listen, and a push in the right direction.” - John Crosby

When I became interested in educational research about 10 years ago, nobody in my department was doing this type of work. I had no idea where to start. I was so lucky to find mentorship outside of my institution from Dr Randy Schell at the University of Kentucky. He helped me to start my first project, obtain my first grant, publish this work, and meet so many other educational researchers in our field. The SEA has made it so much easier to connect with a mentor outside of your institution to help with educational research. I was fortunate to be partnered with Dr Christine Vo at the University of Oklahoma as my SEA Mentee this past year. It has been so fun for me to see all the impressive things she is accomplishing! If you are interested in pursuing educational research but don’t have mentors within your department, join the SEA Mentorship Program! It is a tremendous opportunity to grow your career.

As an SEA research mentor, I have had the privilege of working closely with Dr. Oluwakemi Tomobi over the past year on her anesthesia consent project, and I can attest to the value and benefits of this program. August 2023: Invitation to the SEA Research Mentorship Program (2023-2024 Cycle)The SEA Research Committee has organized the research mentorship program since 2022, provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. The goal is to support a clinician-educator who needs longitudinal coaching/mentorship on her/his educational research study for publication. We are now inviting applicants to the research mentorship program in 2023-2024 cycle: https://www.seahq.org/research-mentorship-program Heather A. Ballard, MD: SEA Research Mentee (2022-2023 Cycle) Have you ever had a project that you were eager to launch, but found yourself lacking the necessary resources and mentorship to bring it to fruition? If so, then the Society for Education in Anesthesia's research mentor program is tailor-made for you. Personally, I consider myself incredibly fortunate to have been invited to join as a mentee and to be paired with the esteemed medical education researcher, John Mitchell. Our initial objective was to transform my SEA abstract, titled "Using Simulation-based Mastery Learning to Enhance Difficult Conversation Skills," into a scholarly work. I'm thrilled to announce that it is scheduled to be published in the esteemed Journal of Education in Perioperative Medicine next month. Through regular meetings, I was held to a higher level of accountability and had the invaluable opportunity to bounce ideas off John and engage in collaborative projects. Our mentor-mentee relationship has yielded exceptional productivity, resulting in three publications and two national presentations. I eagerly anticipate continuing my work with John and paving the way for future SEA mentees. If you are contemplating joining this program, I wholeheartedly encourage you to apply. The program offers the essential components necessary to advance in the field of academic medical education: unparalleled opportunities, invaluable mentorship, and fruitful collaboration. John D. Mitchell, MD: SEA Research Mentor (2022-2023 Cycle) I wanted to update you on the research journey that my SEA research mentoring partner, Dr. Heather Ballard, has embarked on. August 2022: The Best Trainee Abstract Awards (New Program Announcement!)The SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. (New Program Announcement)

Best Trainee Abstract Awards

Awards:

Reason for the awards:

Expected outcome:

Eligibility:

Selection criteria:

Special considerations:

Program Administrators: July 2022: Introduction of the SEA Research Mentorship ProgramThe SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. Introduction of the SEA Research Mentorship Program Needs Assessment:

Goal: Support a clinician-educator who needs a longitudinal coaching/mentorship on her/his educational research study for publication Fei Chen, PhD, MEd Viji Kurup, MD Susan Martinelli, MD John Mitchell, MD (available as of September 2022) Ted Sakai, MD, PhD, MHA, FASA Application Process: Since this program is new, we invite the mentees from the abstract submitters for the SEA Spring meetings. Application or inquiry to [email protected] & [email protected]. Mentorship Processes:

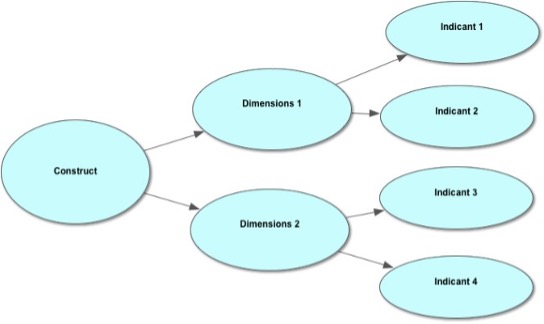

Program Administrators: June 2022: Education Research - Foundations and Practical AdviceThe SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. This month, Dr. Pedro P. Tanaka (Clinical Professor, Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine) shares an overview of Entrustable Professional Activities and provides tips on how you can translate it in your educational research. Translating Entrustable Professional Activities into Education Research Summary Designing a scholarly project on assessment start by addressing the theoretical perspective which demonstrates the philosophical orientation of the researcher that guides their research. Conceptual frameworks represent ways of thinking about a problem or a study, or ways of representing how complex things work. They help to identify and clarify what matters for the study. In this article we discuss how to structure Entrustable Professional Activity (EPA) as a validation research project. We start from the theorical perspective, followed by describing which conceptual frameworks could be used for development, implementation, and validation of an EPA-aligned workplace-based assessment tool. Conceptual frameworks represent ways of thinking about a problem or a study, or ways of representing how complex things work (Bordage, 2009). A. Epistemological Perspective At the core of instrumental epistemology is a view of knowledge as effective action – as the capability to act on and in the world (Bagnall and Hodge, 2017). The ends, though, to which action is directed, are essentiallyexternal to the epistemology, being drawn from the prevailing cultural context, rather than the epistemology itself. Such knowledge is essentially functional in nature, in that the applied knowledge makes it possible to do certain things in particular ways (Bagnall and Hodge, 2017). Education evidencing instrumental epistemology focuses on learners’ engagement in learning tasks underspecific conditions (Bagnall and Hodge, 2017). It is directed to developing highly valued individual action: highly skilled or highly capable individuals in the case of competence-based approaches to education and action (Bagnall and Hodge, 2017). Criteria for assessing education attainment are predetermined by thelearning task as being demonstrable and measurable – centrally, skills and capabilities in the case of competence-based education – related to the pre-specified conditions (Jesson et al., 1987). Assessment is either wholly or substantially performance based, with criteria drawn from the specificationsrecorded in competence articulations (Tovey and Lawlor, 2004). From a psychometric point of view, assessment of learners the workplace is notoriously difficult. It relies on subjective impressions of medical professionals, often not trained in assessment and on test circumstances that cannot be standardized. Medical competence is in part context dependent, and the purpose of the assessment is typically not to know how trainees have performed in the past, but to predict how they will perform in the near future (tenCate et al., 2015). B. Instrument Development Framework The theoretical concept of Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) can be evaluated based on psychometric assumptions described by Thorkildsen (2005a). The following definitions are applicable when creating an assessment instrument:

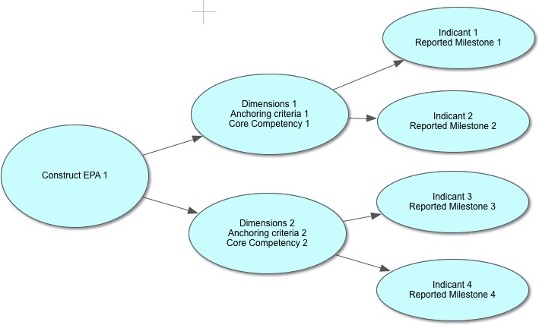

Figure 1. Deductive model of construct, dimensions, and indicants

EPAs can be used as a construct that incorporates different competencies, also known as corecompetencies by ACGME (dimensions). The ACGME framework was developed to address fragmentation and lack of clarity in existing postgraduate programs (Batalden et al., 2002), to enhance assessment ofresident performance, and to increase use of education outcomes for improving resident education (Swing, 2007). The ACGME framework consists of six general competencies, each with a series of sub-competencies. The idea of competencies can be considered as outcome indicators of the education process. The milestones for each competency may serve as definitions, for demonstrations of achievement for that particular competency (indicants). One can map an EPA to domains of competence, competencies within the domains, and their respective milestones. We must be able to both see integrated performance (the EPA) and diagnose the underlying causes of performance difficulties (the competencies and their respective milestones) to help learners continually improve. A construct is a concept, model, or schematic idea. The term latent means ‘‘not directly observable.” In ourmodel for assessment, EPA is the construct, or a latent construct, defined as a variable that cannot be measured. The inability to measure a construct directly represents a measurement challenge. Social scientists have addressed this problem using two critical philosophical assumptions. First, they assume that although systems to measure constructs are completely man-made, the constructs themselves are real and exist apart from the awareness of the researcher and the participant under study. The second assumption is that although latent constructs are not directly observed, they do have a causal relationship with observedmeasures (McCoach, Gable, and Madura, 2013). The operational definition describes the procedures we employ to form measures of the latent variable(s) to represent the construct or concept of interest. In the social sciences, latent variables are often operationalized through the use of responses to questionnaires orsurveys (Bollen, 1989). In this example the variables dimension (core competencies) and indicators (reported milestones) are operationalized through a content validation of the EPAs (Figure 2). Figure 2. Mapping EPAs to ACGME milestones

Affective measurement is the process of ‘‘obtaining a score that represents a person’s position on a bipolarevaluative dimension with respect to the attitude object’’ (McCann, 2017). Similar correlation could be madewhen determining the level of supervision of a resident being able to complete a task independently. C. Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) is a meta-theoretical framework thatprovides a repository of standardized implementation-related constructs that can be applied across the spectrum of implementation research. The CFIR has 39 constructs organized across five major domains, all of which interact to influence implementation and implementation effectiveness. Those five major domains are: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of the individuals involved, and the process of implementation. Eight constructs are identified related to the intervention (e.g., evidence strength and quality), four constructs are identified related to outer setting (e.g., patient needs and resources), twelve constructs are identified related to inner setting (e.g., culture, leadership engagement), five constructs are identified related to individual characteristics (e.g., knowledge and beliefs about the Intervention), and eight constructs are identified related to process (e.g., plan, evaluate, and reflect)(Damschroder et al., 2009). The CFIR provides a common language by which determinants of implementation can be articulated, as well as a comprehensive, standardized list of constructs to serve as a guide for researchers as they identify variables that are most salient to implementation of a particular innovation (Kirk et al., 2015). It provides a pragmatic structure for approaching complex, interacting, multi-level, and transient states of constructs in the real world by embracing, consolidating, and unifying key constructs from published implementation theories(Damschroder et al., 2009). D. Theoretical Domains Framework Describes a comprehensive range of potential mediators of behavior change relating to clinical actions. It thus provides a useful conceptual basis for exploring implementation problems, designing implementation interventions to enhance healthcare practice, and understanding behavior-change processes in the implementation of evidence- based care (Francis et al., 2012). This framework synthesizes a large set of behavioral theories into 14 theoretical domains (i.e., sets ofconstructs; see Table I) that should be considered when exploring health professionals’ behaviors. TheTheoretical Domains Framework posits that factors influencing these behaviors can be mapped to these 14 domains and that each domain represents a potential mediator of the behavior (Cheung et al., 2019). TABLE I. THEORETICAL DOMAINS FRAMEWORK

Commons licensing: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. Hence, two major strengths of the Theoretical Domains Framework are its theoretical coverage and its capacity to elicit a comprehensive set of beliefs that could potentially be mediators of behavior change(Francis et al., 2012). E. Messick’s Validity Framework In Messick’s framework, evidence derives from five different sources: content, internal structure,relationships with other variables, response process, and consequences. Content refers to steps taken to ensure that assessment content reflects the construct it is intended to measure. Response process is defined by theoretical and empirical analyses evaluating how well rater or examinee responses align with the intended construct. Data evaluating the relationships among individual assessment items and how these relate to the overarching construct defines the internal structure. Associations between assessment scores and another measure or feature that has a specified theoretical relationship reflect the relationship with other variables. Consequences evidence focuses on the impact, beneficial or harmful and intended or unintendedimplications of assessment (Cook and Lineberry, 2016).

References:

May 2022: Education Research - Foundations and Practical AdviceThe SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. Key Points

During my residency training, whenever a procedure went particularly well or particularly poorly, an older, wiser anesthesiologist at my institution was fond of saying “Anesthesia is a game of kings and fools.” He cautioned against getting too invested in either success or failure as the next challenge was surely coming to swing you in the other direction. While I don’t think he had ever read Dr. Carol Dweck’s work on Mindset Theory, he understood the dangers of internalizing the outcome rather than focusing on the process, and he created an environment that fostered a growth mindset in his learners. Growth Mindset vs. Fixed Mindset Feedback and the Origin of the Mindsets Developing a Growth Mindset Assessing Mindset Regardless of whether you apply mindset theory to your next curriculum or education research project or just use it in your day-to-day interactions with trainees, keep this guide in mind to create an environment and provide feedback that encourages a growth mindset! Lauren Buhl, MD, PhD April 2022: Education Research - Foundations and Practical AdviceThe SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. This month, Dr. Pedro Tanaka (Clinical Professor of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Stanford University Medical School) shares a Roadmap from Competence to Entrustable Professional Activities. A Roadmap from Competence to Entrustable Professional ActivitiesCompetence Mulder suggests that ‘professionals are competent when they act responsibly and effectively according to given standards of performance’ (Mulder, 2014). In other words, a meaningful distinction exists between acting in a specific way and possessing a capability for those actions, i.e., competence. Characterizing an action as competent depends on the observer’s point of view. Regardless if there are standards for assessing competence, an observer can never step out of their lifeworld to make an objective assessment, hence it is not possible to judge competence, and predict competent behavior via observing the performance. A key point about the components of competence is that, unlike performances, they cannot be precisely specified (Vonken, 2017). These foundational components of competence are attributes, or properties of people, such as capabilities, abilities, and skills, where precision in describing them is not attainable (Hager, 2004). Hager comments, “It is performance rather than human capabilities that can be sufficiently and meaningfully represented in statement form; then these proponents of competence have mixed up different categories of items, thereby committing the first pervasive error about competence. It is precisely because performance is observable/measurable/assessable, while the capabilities, abilities and skills that constitute competence are inaccessible, that judging competence always involves inference” (Hager, 2004). Performance is nothing else but observed behavior, which is assessed as competent. The description of competence, from the beginning, summarizes many discussions, to explain what makes an action competent. According to that discussion, acting competently means to act ‘responsibly and effectively’ and ‘to deliver sustainable effective performance’. The greatest challenge in Competency Based Medical Education (CBME) has been developing an assessment framework that makes sense in the workplace. To be meaningful, such a framework should be specific enough in its description of the behaviors of learners at various developmental stages that it allows for a shared mental image of performance for learners and assessors alike. Competencies address learners’ abilities to integrate knowledge, skills, and attitudes around a specific task. Milestones are brief narrative descriptions of the behaviors that mark given levels of competency, providing a standardized model of behaviors trainees are expected to demonstrate as the progress along the developmental continuum, which spans from education and training to practice. Competencies and their milestones both lack context. Trainee assessment, however, is directly dependent on the clinical context, thereby creating a challenge to meaningful assessment. Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs) provide the context that competencies and their milestones lack and define the common and important professional activities for a given specialty. In the aggregate, they define the clinical practice of the specialty. In contrast to milestones, which provide a granular look at individual behaviors embedded within a given competency, EPAs provide a holistic approach in which assessors view performance through a “big picture” lens to determine whether a learner can integrate competencies to safely and effectively perform the professional activity. EPAs provide context to meaningful assessment missing from competencies and milestones. However, EPAs without the competencies and milestones suffer from the absence of a shared behavioral narrative of what performance looks like along the developmental continuum. These narratives provide language on which actionable feedback for trainee development is built (Schumacher et al., 2020). The Concept of Entrustable Professional Activity An EPA can be defined as a unit of professional practice that can be fully entrusted to a trainee, as soon as they have demonstrated the necessary competence to execute this activity unsupervised (ten Cate et al., 2015). Two aspects of this definition have implications for assessment, 1) a focus on units of professional practice which influences an assessment’s blueprint, the test methods employed, and 2) how scores are calculated and a focus on decisions of entrustment, which have implications for the way standards are set. At the postgraduate level, there is tension between the granularity of the competencies and the integrated nature of the EPAs, and work on faculty judgments about entrustment is needed (Tekian et al., 2020). EPAs were created based on the assumption that it is essential to assess competencies and competence. The premises of formulating EPAs were that identification of ‘entrustable’ professional activities could help program directors and supervisors in their determination of the competence of trainees. The use of EPAs may lead to fixed- length variable outcome programs (fixed training time for graduate medical education) evolving to fixed-outcomes (core competencies) and variable-length programs (ten Cate, 2005). Some specific attributes of EPAs are valuable before an entrustment decision is made such as they:

EPAs can be the focus of assessment. Assessment of a trainee’s performance of an EPA uses an expert supervisor’s subjective, day-to-day observations of the trainee in relation to a competency benchmark. This guided direct observation of learners has potential for more accurately assessing a trainee’s performance and more meaningfully providing a panoramic view of trainee performance. The question is how we “entrust” our trainee to perform a particular EPA. Trust In a medical training setting, trust is best understood to mean “the reliance of a supervisor or medical team on a trainee to execute a given professional task correctly and on his or her willingness to ask for help when needed.” (ten Cate et al., 2016) Trust by a supervisor reflects demonstration of competence and reaches further than a specific observed competence, is that it determines when to entrust an essential and critical professional activity to a trainee. Trusting residents to work with limited supervision is a deliberate decision that affects patient safety. In practice, entrustment decisions are affected by four groups of variables: 1) attributes of the trainee (e.g., tired, confident, level of training); 2) attributes of the supervisors (e.g., lenient or strict); 3) context (e.g., time of the day, facilities available); and 4) the nature of the EPA (e.g., rare, complex versus common, easy) (ten Cate, 2013). These variables reflect one of the four conditions for trust (ten Cate, 2016), which is competence, including specific competencies and associated milestones; integrity (e.g., benevolence, having favorable intentions, honesty and truthfulness); reliability (e.g.working conscientiously and showing predictable behavior) and humility (e.g., discernment of own limitations and willingness to ask for help when needed) (Colquitt, Scott, and LePine, 2007) that are described as dominant components of trustworthiness of a medical trainee (ten Cate, 2017). There are three modes of trust in clinical supervisor–trainee relationships: presumptive trust, initial trust, and grounded trust (ten Cate et al., 2016). Presumptive trust is based solely on credentials, without prior interaction with the trainee. Initial trust is based on first impressions and is sometimes called swift trust or thin trust. Grounded trust is based on essential and prolonged experience with the trainee. Entrustment decisions (whether or not to trust the learner to perform the task) should be based on grounded trust. Entrustment Decisions Entrustment decision making—that is, deciding how far to trust trainees to conduct patient care on their own —attempts to align assessment in the workplace with everyday clinical practice (ten Cate et al., 2016). Ad hoc entrustment decisions can be made daily on every ward or clinic and in every clinical training institution. They are situation dependent, and based on supervisors’ judgments regarding the case, the context and the trainee’s readiness for entrustment. Summative entrustment decisions are EPA decisions that reflect identification of competence, supplemented with permission to act unsupervised, and a responsibility to contribute to care for one unit of professional practice, at graduation standards level. The condition is that the trainee has passed the threshold of competence and trustworthiness for an EPA at the level of licensing. Clinical oversight remains in place for trainees. Readiness for indirect supervision or unsupervised practice should include the specific EPA-related ability and the three other trust conditions: integrity, reliability and humility. The confirmed general factors that influence entrustment of a given professional task: the trainee’s ability; the personality of the supervising physician; the environment and circumstances in which the task is executed; and the nature and complexity of the task itself should be taken in consideration for assessment (Sterkenburg et al., 2010; Tiyyagura et al., 2014). The literature suggests a fifth category or factor (Hauer et al., 2014) to determine whether an ad hoc decision may be taken to entrust a trainee with a new and critical task in the workplace. The relationship between trainee and supervisor has been suggested as a category for entrustment decisions, with its own factors, as this appears to be a condition for the development of trust. There is a long list of factors in each category summarized by the conceptual framework of the entrustment decision-making process (Holzhausen et al., 2017). The assessment of these qualities in a trainee requires longitudinal observation, preferably across different contexts. More recent major themes were elucidated thorough understanding of the process, concept, and language of entrustment as it pertains to internal medicine. These include:

Level of Supervision “Entrustability scales” defined as behaviorally anchored ordinal scales based on progression to competence reflect judgments that have clinical meaning for assessors and have demonstrated the potential to be useful for clinical educators (Rekman et al., 2016). Raters find increased meaning in their assessment decisions due to construct alignment with the concept of EPA. Basing assessments on the reference of safe independent practice overcomes two of the most common weaknesses inherent in work-based assessment (WBA) scales - central tendency and leniency bias (Williams, Klamen, and McGaghie, 2003) - and creates freedom for the assessor to use all categories/numbers on the scale (Crossley et al., 2011). A limitation that entrustment-aligned tools share with all WBA tools is their inability to completely account for context complexity (Rekman et al., 2016). Additionally, tools using entrustability scales benefit if raters are able to provide narrative comments (Driessen et al., 2005). These narrative comments support trainee learning by giving residents detailed explanations and contextual examples of performance and help collate results of multiple WBAs to make more informed decisions. EPAs can be the focus of assessment. The key question is: Can we trust this trainee to conduct this EPA? The answer may be translated to five levels of supervision for the EPA, defined below (ten Cate 2013; ten Cate and Scheele 2007, ten Cate et al., 2016).

Entrustment and supervision scales, or just ‘entrustment scales, are ordinal, non continuous scales, as they focus on decisions and link to discreet levels of supervision (ten Cate, 2020). Conceptually, entrustment-supervision (ES) scales operationalize the progressive autonomy for which health professions education strives. ES scales can guide teacher interventions within what Vygotsky has named the "Zone of Proximal Development" of a trainee (ten Cate, Schartz, and Chen, 2020). ES scales should therefore reflect the extent of permissible engagement in actual professional practice, rather than being a measure of competence. References: Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: a meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of applied psychology, 92(4), 909. Crossley, J., Johnson, G., Booth, J., & Wade, W. (2011). Good questions, good answers: construct alignment improves the performance of workplace‐based assessment scales. Medical education, 45(6), 560-569. Driessen, E., Van Der Vleuten, C., Schuwirth, L., Van Tartwijk, J., & Vermunt, J. D. H. M. (2005). The use of qualitative research criteria for portfolio assessment as an alternative to reliability evaluation: a case study. Medical education, 39(2), 214-220. Pedro P. Tanaka, M.D., Ph.D. (Medicine), M.A.C.M., Ph.D. (Education)

March 2022: Education Research - Foundations and Practical AdviceThe SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. This month, Dr. Lauren Buhl (Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology at Harvard Medical School and Chief of Anesthesia at Beth Israel Deaconess Hospital - Needham) shares an overview of Deliberate Practice and Expert Performance and provides tips on how you can apply them in your own research. While Hollywood may celebrate the prodigy, the genius, and the savant who seem able to perform at an elite level with barely a hint of effort, the rest of us have long recognized that achieving a high level of performance in nearly any domain requires both experience and practice. The questions that have intrigued modern researchers are how much experience, and what kind of practice? It is clear that duration of experience alone cannot explain the vast individual differences in professional performance, and some forms of practice are clearly more efficient and effective than others. K. Anders Ericsson was a Swedish psychologist whose career revolved around these questions, and his ideas about deliberate practice and expert performance earned him a reputation as “the world’s expert on expertise.” The Learning Curve Ericsson proposed three curves along which performance might track with experience. While all new tasks and activities initially require some amount of cognitive focus, the goal for most day-to-day tasks is to reach a socially acceptable level of performance that becomes autonomous (e.g., peeling a potato). Expert performance, however, maintains that initially high level of cognitive focus, perfecting each detail of the task. If that focus is lost and we slip into autonomous performance along the path to expertise, we may end up with arrested development somewhere short of expert performance. To avoid that fate, practitioners who wish to attain an expert level of performance must continue to find opportunities for and dedicate themselves to deliberate practice. In medicine, those opportunities may present themselves readily during training, but often require far more effort to seek out after graduation. 10,000 Hours Studies of elite chess players, musicians, and professional athletes have converged on the idea that about 10,000 hours of deliberate practice is necessary to achieve expert level performance. This number has been corroborated using practice diaries of elite musicians and chess players and tracks with the typical age when peak performance is reached in numerous sports. It is also just a little less than the clinical hours of a typical ACGME-accredited Anesthesiology residency – although arguably not all of those hours are spent on deliberate practice. Criteria for Deliberate Practice What, then, constitutes deliberate practice and contributes to those 10,000 hours? Ericsson and colleagues reviewed many kinds of practice activities to identify those that were highly correlated with expert performance and defined three criteria for deliberate practice:

Applying Deliberate Practice in your Teaching and Research When applying and studying the concept of deliberate practice in your own teaching and research, it is important to break down the broad range of “anesthesia care” into representative, measurable tasks. In general, medical education researchers have focused on three domains of diagnosis and treatment:

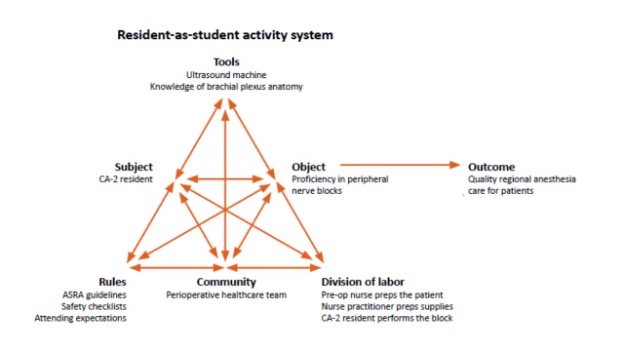

Whether you are researching a new simulator to practice a technical skill or designing a new subspecialty curriculum, consider applying the concepts of deliberate practice to help your learners stay on the road to expert performance! February 2022: Education Research - Foundations and Practical AdviceThe SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. As we enter the season of rank lists and residency and fellowship matching, many of us are awash in discussions of holistic review processes and anti-bias training, while little attention is paid to the more insidious yet pervasive problem of noise in human judgement. A new book by Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman titled “Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgement” seeks to address this imbalance as it reminds us again and again, “Where there is judgement, there is noise, and more of it than you think.” Bias vs. Noise Most of us are familiar with the distinct concepts of accuracy and precision in measurement. Matters of judgement can be viewed as measurements in which the instrument used is the human mind. In this sense, miscalibration is analogous to bias, whereas imprecision is analogous to noise. Bias feels like an identifiable problem that we can measure and address with proper training and vigilance, and the elimination of bias carries a heavy moral imperative. As such, addressing bias receives nearly all of our attention in discussions about improving professional judgements. Noise, on the other hand, seems like an abstract statistical concept with no intrinsic moral imperative and no specific path to combat it. The contribution of noise to unfairness and injustice in world, however, can be equal to or even surpass that of bias, and efforts to reduce noise should receive considerably more attention than they are currently paid. Is noise a bad thing? Some amount of noise is judgement is arguably not a bad thing. What kind of world would it be if everyone judged everything in exactly the same way every single time? We understand that unlike matters of fact on which no reasonable person would disagree (e.g., the sun will rise in the East tomorrow), judgement allows for a bounded range of disagreement. The problem is that what most people consider to be an acceptable range of disagreement is much smaller than the actual ranges of disagreement observed in the world. In a study of asylum cases randomly assigned to different judges, the admission range was between 5% and 88%, a veritable lottery. While I have not found a similar study of anesthesia residency application reviewers and applicants offered an interview, the range is probably just as shockingly large. Types of noise Noise can come from many sources, but it is helpful to divide total system noise into level noise and pattern noise. Level noise can be measured using the variability of the average judgements made by different people and is something we all recognize in the existence of harsh reviewers and lenient reviewers. Even within our own abstract scoring processes at SEA, it is clear that some reviewers give consistently lower scores across all abstracts, while other reviewers give consistently higher scores. Level noise is commonly related to ambiguity in scoring systems anchored by words such as “mostly” or “sometimes” that mean different things to different people rather than anchoring with more specific examples. When level noise is removed from total system noise, what remains is pattern noise. Unlike level noise where both harsh and lenient reviewers may still rank abstracts in the same order, pattern noise produces different rankings based on individual predilections and idiosyncratic responses of reviewers to the same abstract. In general, pattern noise tends to be larger than level noise as a component of total system noise. Some pattern noise is fixed, as when reviewers give harsher scores to abstracts within their area of expertise and more lenient scores to abstracts that are more removed from their own work. On the other hand, some pattern noise is variable, as when the same reviewer might give different scores to the same abstracts in the morning than in the afternoon, when the weather is bright and sunny vs. gray and gloomy, or after their favorite football team loses. The “mediating assessments protocol” to minimize noise At one extreme, the complete elimination of noise in judgements would require an algorithmic approach that carries its own risk of systematic bias and is often unsatisfying to those being judged, who feel like the specifics of their individual situation are not being seen or heard, and to those doing the judging, who feel like their hands are tied without the ability to exercise some amount of discretion. A more realistic goal is to minimize noise by exercising decision hygiene. One such approach for professional judgements (e.g., evaluation of residency applicants) is the mediating assessments protocol designed by Daniel Kahneman and colleagues. The protocol consists of six steps: 1) Structure the decision into mediating assessments or dimensions in which it will be measured. In the context of residency applicants, decisions are commonly broken down into mediating assessments such as academic achievements, evidence of resilience and grit, and overlap of applicant goals with program strengths. 2) When possible, mediating assessments should be made using an outside view. This “outside view” relies on relative judgements (i.e., this applicant’s test scores are in the 2nd quartile with respect to our pool of applicants) as opposed to fact-based judgements (i.e., this applicant has good test scores). 3) In the analytical phase, the assessments should be independent of one another. Ideally, the reviewers assessing academic achievement should be different from the reviewers assessing resilience and grit and different from the reviewers assessing the overlap of applicant goals with program strengths. 4) In the decision meeting, each assessment should be reviewed separately. 5) Participants in the decision meeting should make their judgements individually, then use an estimate-talk-estimate approach. This approach involves individuals giving their initial ratings in a secret vote, sharing the distribution of ratings to guide discussion, then individuals giving their subsequent ratings in another secret vote, thereby gaining the advantages of both deliberation and averaging independent opinions. 6) To make the final decision, intuition should be delayed, but not banned. By frontloading the process with careful analytics and independent assessments, intuition becomes more firmly grounded in fact-based metrics and thoroughly discussed ratings than it would have been if applied at the beginning of the process. The difficulty lies in applying this process for decision hygiene to an expansive endeavor like residency applications, where programs may be confronted with 1,500 applications and limited time and personnel to consider them. Certainly, aspects of decision hygiene may still be applied, such as linear sequential unmasking where individual parts of the application are revealed to reviewers sequentially (i.e., essay, then letters of recommendation, then test scores, then medical school, etc.), thereby limiting the formation of premature intuition. Alternatively, the full mediating assessments protocol may be achievable on a smaller scale (e.g., only the applicants on the cusp of being ranked to match). While the best way to address noise in judgements may vary, noise reduction should not be overlooked in favor of focusing on bias reduction, and in fact, reducing noise may make bias more readily identifiable and, thus, correctable. Lauren Buhl, MD, PhD January 2022: Education Research - Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT)The SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. This month, Dr. Lauren Buhl (Instructor of Anesthesiology at Harvard Medical School and Associate Residency Program Director at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) shares an overview of Cultural Historical Activity Theory (CHAT) and provides tips on how you can apply it in your own research. In his commencement speech at Kenyon College in 2005, David Foster Wallace began with a story about some fish: There are two young fish swimming along who happen to meet an older fish. The older fish nods at them and says: ‘Morning boys, how’s the water?’ The two young fish swim on for a bit and then eventually one of them looks over at the other and asks: ‘What the hell is water?’ This parable nicely illustrates how we often become overly focused on a single subject or perspective and fail to recognize the complex system surrounding us. Cultural historical activity theory (CHAT) can provide a lens through which to view and analyze these complex systems in the context of medical education research, curriculum design, and performance evaluation. What is Cultural historical activity theory (CHAT)? First developed by Vygotsky in the late 1970s and later expanded in the field of medical education by Engeström, CHAT starts from the basic unit of the activity system to outline the many interdependent relationships that make up a complex system designed to achieve an overarching outcome or end product. Consider the example of a CA-2 resident learning to perform peripheral nerve blocks on their regional anesthesia rotation (see figure).

The activity system includes the following components:

Cultural historical activity theory (CHAT): A tool to identify conflicts and tensions The arrows connecting each of these components speak to the ways in which they are all shaped and affected by each other. Naturally, there will be conflicts and tensions within the activity system (e.g., the patient may want the regional anesthesia attending to perform the procedure, but this is at odds with the object of achieving proficiency in peripheral nerve blocks for the CA-2 anesthesia resident). The resolution of these conflicts can provide many fruitful avenues for research, and when the resulting data are viewed in the context of the overall activity system rather than the individual relationships between components, the conclusions can be more nuanced and broadly applicable. There can also be conflict between activity systems, as each subject may find themselves working in multiple activity systems with conflicting objects. If we add a medical student into the example, our CA-2 resident now functions in one activity system as a learner and another activity system as a teacher. These two systems have some overlapping outcomes (professional development) but also some conflicting outcomes (technical skill for resident-as-learner and teaching evaluations for resident-as-teacher). Cultural historical activity theory (CHAT): How to apply it to your research Using CHAT, medical educators and researcher can develop and study interventions that address these conflicts (i.e., only pairing medical students with more senior residents or combining teaching evaluations from multiple perspectives rather than just from the medical student). I hope this description of CHAT will help you analyze the complex circumstances in which we work, teach, and learn using activity systems to help identify areas of conflict and tension that provide great starting points for new approaches and research. November 2021: Education Research - Foundations and Practical Advice: Self-Determination Theory (SDT)The SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. This month, Dr. Lauren Buhl (Instructor of Anesthesiology at Harvard Medical School and Associate Residency Program Director at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center) shares an overview of self-determination theory (SDT) and provides tips on how you can apply it in your own research. Motivation and the ways in which we can create it, maintain it, and direct it into useful behaviors is a constant in nearly all domains of life. As such, social scientists and psychologists have generated an array of theories describing the motivational process and suggesting how it might be harnessed to produce desired outcomes. In medical education, motivation is critical to achieving our goal of promoting learning among our students. Self-determination theory (SDT) is widely considered to be the dominant theory in the psychology of motivation, and as such, it is often a useful lens through which to consider curriculum development and research projects in medical education. First developed by Edward Deci and Richard Ryan at the University of Rochester in the early 1970s, SDT stems from the principle that humans are growth-oriented and observations that we experience improved performance, achievement, and well-being when our behaviors are internally motivated rather than driven by an external source. A goal for medical educators, then, should be to create contexts in which motivation and behavior regulation can be moved from external sources to fully internalized. This continuum is described as follows:

This process of internalization of motivation and behavioral regulation requires the satisfaction of three innate psychological needs: a need for autonomy, a need for competence, and a need for relatedness. When attempting to apply SDT, the question you might ask yourself while conducting an observational study or designing a research project is, “How well are these psychological needs being met?” Observational studies

I hope this description of SDT and its many potential applications will aid you when designing your next curriculum intervention or research project or even just in your day-to-day teaching interactions! October 2021: Education Research - Foundations and Practical Advice: SEAd Grant ApplicationThis month, Drs. Nina Deutsch (Associate Professor of Anesthesiology and Pediatrics; Vice Chief of Academic Affairs; Director, Cardiac Anesthesiology, Children’s National Hospital) and Franklyn P. Cladis (Professor of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine; Program Director, Pediatric Anesthesiology Fellowship; Clinical Director, Pediatric Perioperative Medicine, The Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC) share the tips to make your SEAd Grant Application more competitive in the review process. The Society for Education in Anesthesia (SEA) SEAd Grant provides an outstanding opportunity to fund a starter education research project led by aspiring faculty members of SEA that have no previous funding. First awarded in 2016, the $10,000 SEAd Grant is bestowed annually and stipulates that the recipient be given non-clinical time by their department to complete the project. Here, we provide you with practical tips to help you to submit a competitive SEAd Grant application. The objectives are to stress the prerequisites for the grant submission, what constitutes a strong application, and the key schedule for your grant proposal submission. 1) Prerequisites of SEAd Grant submission Your proposed project must be related to education! We will not accept an application purely on clinical research or basic research. Applicants must:

2) What Constitutes a Strong Submission The SEAd Grant was created with the intention to fund innovative education research projects which will improve the learning opportunities of trainees, medical students, and/or faculty members. Some key points that make applications stronger during consideration:

3) Key Schedule The SEAd Grant application process will consist of two phases. The selection committee will review all Phase 1 applications and will invite the top three applicants to complete Phase 2. Phase 1 should include the following and must be submitted to [email protected]:

Phase 1 begins 10/01/2021 with the deadline of 01/03/2022. From 01/03/2022 through 01/21/2022, the Selection Committee will review the abstracts and invite the top three abstracts to complete Phase 2. Applicants will be notified of a decision around 1/28/2022. Phase 2 will include the following and must be submitted to [email protected]:

Phase 2 of the application process will occur from 01/28/2022 with the deadline of 02/28/2022. The recipient of the SEAd Grant is expected to participate in the SEA Spring Meeting (April 8, 2022 to April 10, 2022). At this meeting, the recipient will be announced during the awards session on April 9, 2022. We hope the above tips will be helpful to you as you write your SEAd Grant proposal. We are looking forward to receiving your submission! September 2021: Education Research - Foundations and Practical Advice: SEA Meeting Abstract and PresentationThe SEA Research Committee provides practical advice for planning, executing, and submitting your scholarly works in educational research and curriculum development. Alternatively, we feature a summary of educational theories to broaden your foundation in educational research and curriculum development. This month, Drs. Deborah Schwengel (Associate Professor of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine) and Melissa Davidson (Professor of Anesthesiology, the University of Vermont Medical Center) share the tips to make your Spring SEA meeting abstract and presentation more completive in the review process. This piece aims to provide you practical tips to help you construct a competitive abstract for the Spring SEA meeting. The objectives are to stress the prerequisites for the SEA Spring meeting abstract submission, what constitutes a strong abstract in the “Innovative Curriculum” section and “Research” section, respectively, and the key schedule for your abstract submission to the 2022 Spring SEA meeting on April 8-10, 2022, at Pittsburgh, PA. 1) Prerequisites of SEA Spring meeting abstract submissionYour abstract must be related to education! Be aware, especially if you are planning to submit a research abstract. We will not accept an abstract purely on clinical research or basic research. 2) Innovation Curriculum AbstractThis category welcomes any “innovative curriculum” which has improved the learning opportunity of trainees, medical students, and faculty members. However, to write a solid abstract to get into the prestigious Oral Presentation, where the Philip Liu Best Abstract Award with a cash prize of $1,000 will be chosen, you would like to demonstrate the evidence of curriculum implementation. A survey of the learners’ impressions or a report of before-and-after knowledge gain (e.g. pre-/post-test) could be evidence of curriculum implementation. Attached here is the Philip Liu Best Innovative Curriculum Abstract Award winner's submission at the 2021 SEA Spring meeting for your reference. If you have multiple outcomes to present, you could consider submitting your abstract to Research Abstract Category instead. 3) Research AbstractThe SEA Research Committee is updating the scoring rubric to differentiate the strengths and weaknesses of the submitted abstracts to select candidates for the Philip Liu Best Research Abstract Award. We believe the best advice to you is to share our core scoring rubric at this point; thus, you will have an opportunity to review and improve your abstract critically. We have set two evaluation components: Analytic and Holistic. Analytic evaluations:

Holistic evaluations:

We admit you cannot address the Holistic evaluations directly; however, the list of the items in the Analytic evaluations could help you review your abstract before submission critically. Attached here is the Philip Liu Best Research Abstract Award winner's submission at the 2021 SEA Spring meeting for your reference. 4) Key Schedule

We hope the above tips would be of help for your abstract writing. We are looking forward to receiving your abstract submission! |

Christine Vo, MD, FASA: SEA Research Mentee (2022-2023 Cycle)

Christine Vo, MD, FASA: SEA Research Mentee (2022-2023 Cycle)  Oluwakemi Tomobi, MD, MEHP: SEA Research Mentee (2022-2023 Cycle)

Oluwakemi Tomobi, MD, MEHP: SEA Research Mentee (2022-2023 Cycle) Susan Martinelli, MD, FASA: SEA Research Mentor (2022-2023 Cycle)

Susan Martinelli, MD, FASA: SEA Research Mentor (2022-2023 Cycle) Fei Chen, PhD, MEd, MStat: SEA Research Mentor (2022-2023 Cycle)

Fei Chen, PhD, MEd, MStat: SEA Research Mentor (2022-2023 Cycle)

Pedro P. Tanaka, M.D., Ph.D. (Medicine), M.A.C.M., Ph.D. (Education)

Pedro P. Tanaka, M.D., Ph.D. (Medicine), M.A.C.M., Ph.D. (Education)